The 2025 Bert Roth Award recognises two outstanding works of labour history, each bringing a distinctive approach to documenting workers’ struggles in Aotearoa New Zealand and the Pacific.

Winners:

Lyndy McIntyre, Power to Win: The Living Wage Movement in Aotearoa New Zealand (Otago University Press)

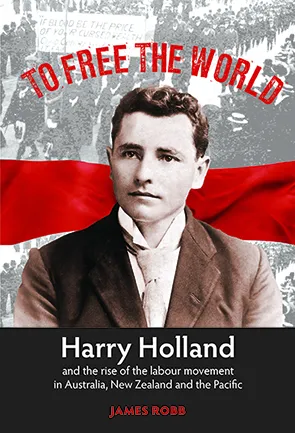

James Robb, To Free the World: Harry Holland and the Rise of the Labour Movement in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific (Steele Roberts Aotearoa)

Both books are extensively researched, well-written and richly illustrated. The judging panel awarded the full Bert Roth Award to both winners in recognition of their significant contributions to labour history scholarship.

Power to Win is an insider’s account of the Living Wage Movement (LWM), the campaign to lift the wages of the most disadvantaged in our workforce – women, Māori, Pacifika, migrants and refugees, and young workers – so they are paid enough ’to meet their needs, enjoy their lives and participate in society’, ‘to thrive, not barely survive’. Lyndy McIntyre documents the impact of post-1984 legislation and the Employment Contracts Act 1991 on union/workers’ bargaining power and the limited effect of industrial action (stop-works, pickets, strikes) on ever-increasing inequities. She welcomed an alternative – and successful – organising model that John Ryall of the Service and Food Workers Union (SFWU) and Muriel Tonoho had experienced with the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) in London.

The process is described by which, from 2012, union activists, members of community organisations and local faith groups from the low-waged workers’ communities – and the low-wage workers themselves – were brought together to target specific employers and engage with them to persuade them to become ‘living wage’ employers. The strategies the LWM developed to sustain the energy and commitment of these participants are also identified: training and refresher training, bringing new people in, fundraising to enable the payment of organisers, and celebrating successes (however partial), are some of them. A window is provided into the lives of many of those involved in the campaign, detailing “the rich diversity of people…who want a better and more just world”. McIntyre pays particular attention to the contribution of the low-wage workers, many of whom knew they could be risking their jobs by speaking out. Their personal accounts of the realities of their hard- struggle lives and jobs had persuasive power.

By 2023, significant numbers of big and small businesses and city and regional councils were accredited living wage employers, the media reported the latest living wage announcements and the term ‘a living wage’ had entered the common vocabulary. One of the reviewers described Power to Win as ‘an important historical record, an engagingly written narrative of people’s lives, a personal memoir and a guidebook for organisers’, summing up succinctly our reasons for making the Award to Lyndy McIntyre.

To Free the World, a biography of a politician, is not the most obvious candidate for an award for labour history, but Harry Holland, leader of the New Zealand Labour Party from 1919 until his death in 1933, was a Socialist, an activist/agitator and an indefatigable writer, making this book a history of labour conditions and labour relations across three decades of struggle in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific, through the lens of a life.

This book is important as the long-awaited antidote to the 1964 biography of a so-called ‘failure’. James Robb’s research on Harry Holland’s earlier life in Australia and the context of his progression from Salvation Army preacher to revolutionary, his record of Holland’s close relationships with Savage, Fraser and Nash, future leaders of the Labour Party, and his attention to the crowds attracted by Holland’s oratory and lining his funeral cortege, offer rather different perspectives on the man.

Robb’s particular contribution, however, is in documenting the international range of labour connections, the relationships across countries and oceans, as illustrated by, for example, the impact of strikes in Britain and the U.S.A. on worker action in Australia; the origins in German socialism and the German Social Democratic Party of Holland’s vision of ‘the one big (workers) party’; the invitation from the Waihi Socialist Party in 1912 which brought Holland to New Zealand; and Holland’s opposition to New Zealand’s ‘petty imperialism’ and to the indenture system in the Pacific, and his support for the Mau in Samoa, who first organised to demand equal pay with Europeans. Harry Holland spoke out and wrote against exploitation and injustice – and was imprisoned, in Australia and New Zealand, for doing so. Robb has accessed that (now-digitised) huge published output; extensive quotations in the text and break-out boxes bring Holland’s voice alive again.

The Short List

This is the twelfth year of the Bert Roth Award, and once again, selecting a winner was a challenge.

We have a very interesting short list, although labour history is an aspect, rather than the focus, in some, and exploitation can be implied, rather than explored. The first four items below have particular resonance in the current political and economic environment.

Geoff Bertram & Bill Rosenberg, ‘The Employment Contracts Act 1991 and the labour share of income in New Zealand: an analysis of labour market trends 1939–2023’, New Zealand Economic Papers, 12 May 2024.

This article contains a wealth of wide-ranging historical statistical data about the labour share of income. Previous data had found a slide in the labour share of income from 1981 onwards, but by using new data about the ‘wage ratio’, the authors demonstrate that the Employment Contracts Act 1991 and benefit cuts were the causes of the decisive downward trend that has continued since.

Aaron Smale, Tairawhiti: Pine, Profit and the Cyclone, Bridget Williams Books Texts.

This short book on the big subject of the way ‘human decisions have amplified nature’s destructive power and the land’s vulnerability’ is based on Smale’s series for Newsroom on the impact of Cyclone Gabrielle. In 1988, Cyclone Bola forced a limit on pastoral farming on the East Coast, but the Crown’s alternative wasn’t restoration of indigenous forest, it was pine plantations on land sold to overseas forestry companies. Smale documents the consequences of colonisation and commercialisation, silt and slash, on land, sea, and mana whenua, the local people.

Cameron Wilkinson, ‘Who Wants to Do Something About Rising Prices?” Consumer protest and the Campaign Against Rising Prices in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1966-1981’, Thesis, University of Waikato.

While the activities of the Campaign Against Rising Prices (CARP) in the 1960s and 1970s is familiar to most readers of Labour History, Cameron Wilkinson’s thesis seeks to place the campaign more securely within the mainstream history of Aotearoa. The campaign, with its use of regional, relatively independent branches, public meetings, pickets, submissions to government, media releases and economic boycotts in order to, at times, successfully challenge successive governments’ economic policy, the differences that arose between city and regional branches, its battle against being portrayed as a communist front, its close ties to the union movement and its delicate dialogue with the wider feminist movement, offer important learnings for community-based activism.

David Williamson and Candice Harris, So How Did We Get Here? A Historical Case Study of Migrant Employment in the New Zealand Hotel Sector, Labour History, Number 127: 125–44.

This article is a succinct and valuable employment relations style overview of the change from corporatism to neoliberalism in the tourist industry and especially in the privatised Tourist Hotel Corporation in the 1980s/1990s. It successfully argues that the ‘double-whammy’ of neoliberal employment relations legislation combined with the globalisation of hotel ownership caused long-lasting de-unionisation, low wages, and increased precarity – especially for migrant hotel workers.

1970s: Decade of Protest, Steele Roberts Aotearoa.

This book of photographs from the exhibition in 2023, and now the archive, is a comprehensive and accessible overview, capturing the breadth of protest in the 1970s (especially in Wellington) and, unusually, including union and worker protest as an important part of it. Each section has a brief introduction and timeline contextualising the following photographs, which are a vivid reminder of how protest action ‘by ordinary people sparked significant progress towards justice and equality’.

Katie Cooper, Rewena and Rabbit Stew: The rural kitchen in Aotearoa, 1800-1940, Auckland University Press.

This well illustrated book tells of ‘how cooking and food production shaped the daily lives of homes and communities of rural Pākehā and Māori’. As a framework it notes that ‘the kitchen is the perfect vantage point from which to examine aspects of everyday life and that the securing and preparation of food is the most vital of human endeavours’. But as well, the human species uses food ‘as a form of communication and a means of marking boundaries and cementing family and community relations’. There are obvious marked differences between Māori and Pākehā which are well illustrated, as well as the technological changes that have occurred in the kitchen during the period covered, from open fire and camp oven, to wood and coal range, to electric stove, with the hangi pit remaining ubiquitous throughout.

Mark Derby, Frontier Surgeon: New Zealand Pioneer Douglas Jolly, Massey University Press.

The Spanish Civil War, which can be seen as the turning point of 20th century history, has long fascinated Mark Derby, in particular the involvement of Kiwi men and women as volunteers. There is no more notable volunteer than NZ surgeon, Doug Jolly. As the war became a modern war, turning to air bombing and more modern artillery and the targeting of civilians, Doug Jolly pioneered methods of dealing with trauma caused by shrapnel, enabling many to survive what would once have been mortal injuries. These methods were then widely adopted by surgeons during WW11. Medical staff are workers and Jolly was a member of an international class of workers who fought fascism, and who are now given full recognition in this well-researched and accessible book.

Angela Wanhalla, Sarah Christie, Lachy Paterson, Ross Webb and Erica Newman, Te Hau Kainga: The Maori Home Front During the Second World War, Auckland University Press.

This important survey, written by a collective of historians and students, reveals how the Second World War and the mobilisation of the 28th Māori Battalion, was a watershed event for Māori, setting the stage for ‘a range of transformations, including post war urbanisation’ as the battalion was supported at home by home defence groups, women’s auxiliaries who undertook fund raising and the preparation of gift parcels for overseas troops, as well as entertaining US troops on leave at tourist spots. Land was developed, Māori men and women were conscripted into essential industries and many were drawn into forestry, food canning and other ventures. This important contribution to the war effort always struggled for, and gained, a limited tino rangatiratanga, with iwi insisting on working parallel to the Pākehā administration rather than being subservient to a singular national programme.

Poata Alvie Mckree, The Handlers.

The Handlers is set in the 1970s, in the Handle room of the Crown Lynn pottery factory in Auckland. Crown Lynn’s Māori workforce was part of the post-war migration to cities; the play focuses on the experiences of Māori women workers. It explores their informal networks of organising that drew on whānau connections, and the tensions between their expectations and obligations and the requirements of factory work. Fictionalising Māori women workers’ struggles makes these important threads of labour history accessible to a different audience.

Tania Mace, The Near West: A history of Grey Lynn, Arch Hill and Westmere, Massey University Press.

This well-researched and beautifully presented history of an area of Auckland which has hosted an abattoir, a brick works, Hellaby’s meat processing and other manufacturing; also hosting of course, the zoo, Western Springs Stadium and the Auckland Trade Union Centre; had John A. Lee as its MP, but also provided organising centres for the Communist Party, the Polynesian Panthers and HART, as for a period, it had a high proportion of Maori and Pacific Islander in its demographic; is now a residential area for the wealthy professional. The book confines its framework to that of heritage rather than exploring a class narrative, but nevertheless, is rich in information and visuals.

The judges for 2025 were Toby Boraman, Claire-Louise McCurdy and Paul Maunder